Group Raises Another Obstacle to Zip Line

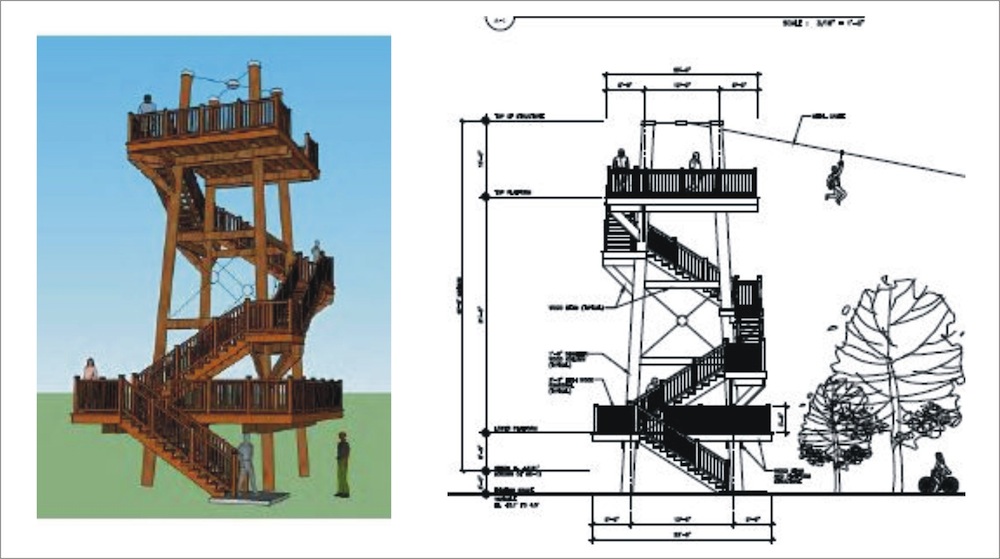

Marathon and the Florida Keys Land and Sea Trust, the operator of Crane Point Nature Center are being taken to court over the issue of the height of some of the hulking towers that would be part of the zip-line course at the site.

Marathon and the Florida Keys Land and Sea Trust, the operator of Crane Point Nature Center are being taken to court over the issue of the height of some of the hulking towers that would be part of the zip-line course at the site.

The dispute centers around a height variance granted by Marathon planning director George Garrett. The current height limit in Marathon is 37 feet; three or four towers (the final number is not clear) are designed to be 46.25 feet. A group of four activists appealed the height variance to the planning commission, which upheld Garrett’s decision on a 4-1 vote in July 2013.

Realtor Morgan Hill, a member of the planning commission at that time, summed up her position as follows:

“When we get in situations like this, I tend to go with the person that helped write it [i.e., Garrett] so on and so forth and how much leeway our planning director has,” she said. “There is a rule book to follow and I have never caught him not following it.”

The group then appealed the planning commission decision to the city council. In December 2013, the council members unanimously upheld the planning commission’s denial of the appeal. On February 10th, attorney Henry Morgenstern petitioned the Circuit Court of the 16th Judicial Circuit for what’s known as a Writ of Certiorari declaring that the city council’s denial of the appeal to the planning commission was illegal and improper. The four appellants include a life member of the Land Trust, a former board member, a current member and a former member. [Full disclosure: my wife is the former member.]

Code issues central to the complaint.

The complaint presents two major issues related to the code.

First, the legal documents question whether the variance meets Marathon’s code, which states that a variance must be “the minimum necessary to make possible the use of the property.” Since Crane Point has been using the property for many years, the legal action questions why they need a height variance to continue to operate the nature reserve.

According to the filing, “it is obvious on its face that the extra-high towers are not ‘necessary to make possible the use of the property.’”

In fact, the Land Trust admitted that the project did not require the variance. The reason for requesting the variance was simply that “the experience of flying [on the zip line] would be enhanced [and the additional height] will provide an exciting experience.”

Marathon’s attorney claimed during the appeals that the planning director can grant variances without any showing of hardship or need under the zoning, even though the code specifies a number of criteria that must be met. According to Morgenstern, such an action would be what is called “spot zoning,” and would be voided as an illegal code provision.

As Morgenstern says in his court filing, “No city official can just arbitrarily hand out permits that allow people to ignore the zoning laws whenever he wants.”

Notice of intent to issue the variance was never given.

Another critical issue the complaint raises involves providing proper notice.

Marathon’s code explains that the way for the planning director to grant an administrative variance is for him to issue a “notice of intent to issue the administrative variance.” The court documents say that, “In this case, the only thing that was provided by the director to anyone was a Notice of Public Hearings, which only states that there will be a public hearing on a ‘request’ for Notice of Intent. Being given notice of a hearing on a request for a million dollars does not provide the million dollars.”

Morgenstern goes on to say that, “There is no indication that any Notice of Intent (versus a request) even exists—in fact, it can’t exist, or it would not have to be requested.”

In the planning department’s evaluation of the appeal to the planning commission, this point was dismissed by stating that the use of “request” was “clearly not the intent of the language used by the City.”

Due process issues play role in the complaint.

The filing also calls into question whether due process was provided. One example has to do with the $1,500 fee required for filing an appeal to the planning commission and again to the council.

As Morgenstern states in the complaint, “This amount is unconscionably high for simply reviewing an existing record, and acts to chill public participation, further denying citizens their right to redress administrative acts as guaranteed by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.”

The court filing adds another level to the worries that the Marathon City Council is obviously feeling. At its January 28th meeting, the Marathon City Council voted unanimously to step back from its participation in the controversial proposal to construct a zip-line course in the Crane Point Nature Center. At that time council members expressed serious concerns about ADA compliance issues, a searing evaluation of the proposal by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and questions about financial management. The city opted, at that point, to give Crane Point nine months to overcome the obstacles.

No court date has, as yet, been set to hear these issues.