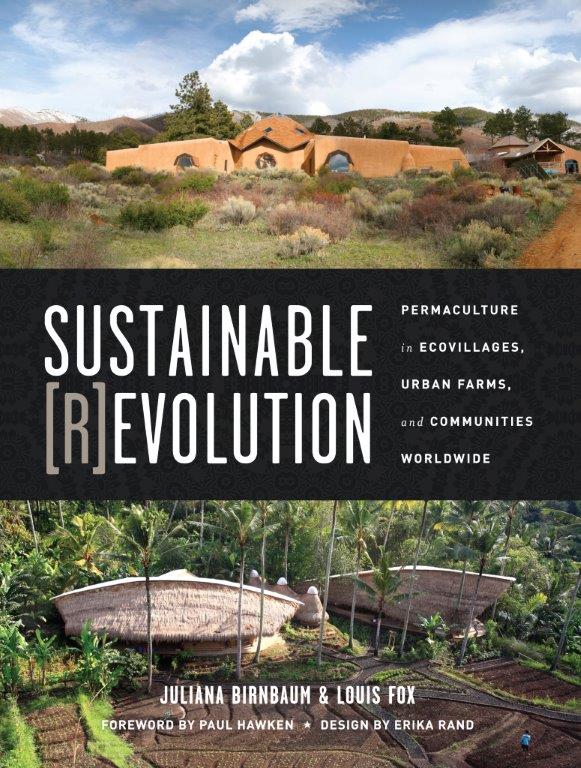

BOOK REVIEW: Sustainable [R]evolution [North Atlantic Books]

Reading Juliana Birnbaum and Louis Fox’s new book is both exhilarating and depressing. Exhilarating because the volume describes in varying detail more than 62 ecovillages, urban farms, and communities from all over the world working toward sustainability.

Reading Juliana Birnbaum and Louis Fox’s new book is both exhilarating and depressing. Exhilarating because the volume describes in varying detail more than 62 ecovillages, urban farms, and communities from all over the world working toward sustainability.

But the paperback is also a downer because it highlights what can be accomplished but isn’t in almost all cities and towns. Here in the Keys for instance, a place that is more than suitable for cutting-edge efforts to reduce human impact upon deteriorating habitats and our climate, nothing of the sort has been contemplated let alone implemented.

The bracket in the title emphasizes how most communities that Birnbaum and Fox choose to profile are still evolving toward that elusive goal of sustainability, one of the latest overused buzzwords, but aren’t there yet. Many, but not all, are employing what is known as permaculture techniques to achieve that goal.

Rachel Kaplan, who wrote the book (Birnbaum and Fox are more editors than writers), defines permaculture’s core principles as, “the working relationships and connections between all things.” In other words, humans seeing the interconnectedness of everything in our environment. The result is an emphasis by the authors and Kaplan [and many others] on small scale, energy- and labor-efficient, intensive systems that use biological resources instead of fossil fuels.

What is sustainability anyway?

Sustainability is an elusive concept. A good working definition comes from the Brundtland Report, which stated that “Humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

Fossil fuels by their very nature can’t be sustainable. We will run out. Whether it’s in ten years or fifty years, the amount in the ground to use is finite. The larger question, of course, is whether we should use them at all given the deteriorating state of the climate that results from the burning of those fuels. And, if the production and use of water and food both remain as they are now, they aren’t sustainable either.

One of the book’s best examples of a site that is employing permaculture principles to achieve sustainability is Auroville Township and Ecovillage in Viluppuram District in Tamil Nadu, India. Described as a “model city for harmonious and environmentally sustainable living…,” the town’s efforts have included “reforestation [urgent in India], efficient resource management, and community cohesion.” The latter is essential for any concerted effort to create a community that achieves the goals that Auroville has set.

For construction of its buildings, Auroville uses a technology called Compressed Stabilized Earth Blocks, which consumes far less energy than conventionally fired bricks and is much more resistant to disasters. Using this method has enabled Auroville to create a community consisting of 45 percent buildings and 55 percent green space. Try to imagine Key West or any Keys community aiming at that sort of split between structures and foliage.

Even more important, Auroville has established the Auroville Earth Institute, which trains others in the techniques of using appropriate technologies, advanced water systems, and, of course, earth building. The Institute fulfills permaculture’s goal of creating connections among people.

There are many such examples in Sustainable [R]evolution. The authors have divided the book into five climate zones so it’s easy to find references to places that are appropriate to where readers might live. This is particularly helpful in the Keys because so many books don’t reference sub-tropical climates.

Unfortunately, the authors also include a few inappropriate examples. One is the Greater World Earthship Community. The structures were originally designed by Michael Reynolds, who was profiled in the excellent documentary Garbage Warriors. While the buildings he has created are models of energy conservation, more sustainable construction, and self-sufficiency, the community that has resulted is no community at all. According to one resident, “it is more a collection of individual homesteads with shared values rather than an intentional community.” That resident could also have noted that the buildings are quite expensive, over a million dollars each.

Sustainable [R]evolution’s many examples of communities all over our planet illustrate that while many are working toward true sustainability, few – or perhaps even none – have achieved that elusive goal. It’s an evolution and not a revolution. Residents of many of those profiled have part-time jobs in nearby towns or cities or have created cottage industries that rely upon external supply chains. While Punta Mona Center in El Caribe Sur, Costa Rica, for instance, produces 90 percent of its own food and conserves water, locals still must drive 35 minutes to deliver what Punta Mona recycles to a center and remove the trash it creates via marine and land transportation.

Whatever they are doing is far better than trucking trash, recycling, and yard waste over one hundred miles in enormous 18-wheelers. Despite all the talk about sustainability here in the Keys, the proposals have been less than inspiring and action almost non-existent. It may not be possible to even come close to sustainability on an island chain that cannot or will not raise its own food, produce its own energy, or even – most disturbing of all – catch and store its own water.

I recommend Sustainable [R]evolution for its inspirational message of what can be achieved. Beautifully designed and laid out with many illustrative photographs, the book is organized around permaculture concepts that are highlighted by helpful internal graphic elements. While it strays off message at times and only provides a sketchy introduction to permaculture, the book is a fine addition to a growing library of information about how we need to change if we have a chance to avert the coming catastrophe.

Or, as permaculture expert David Holmgren, says in the book’s epilogue, “If we are moving into a world of less energy, then the world will re-localize in some form or other. Thinking and action for small and slow solutions, diversity and integration puts you in a stronger position to adapt to the chaos of the future.”